Mikhail Solomonov

Director of the Postgraduate Endodontic Program, Department of Endodontics, Sheba Medical Center, Tel HaShomer (Israel); Lecturer at "Medical Consulting Group" (Moscow)

Director of the Postgraduate Endodontic Program, Department of Endodontics, Sheba Medical Center, Tel HaShomer (Israel); Lecturer at "Medical Consulting Group" (Moscow)

The Microscope Is Not Only an Optical, but Also an Orthopedic, Ophthalmologic, and Even Psychological Tool for the Dentist

Since 1999, I have been working with an endodontic microscope. Over time, my attitude toward it has gone through a full range of states: from frustration (I had to retrain) to dependence (in its absence or malfunction, I feel an overwhelming urge to cancel appointments).

Gradually, I realized all the advantages of using an operating microscope in clinical practice.

As a tool that combines optics with coaxial lighting, the microscope undoubtedly improves the quality of endodontic treatment.

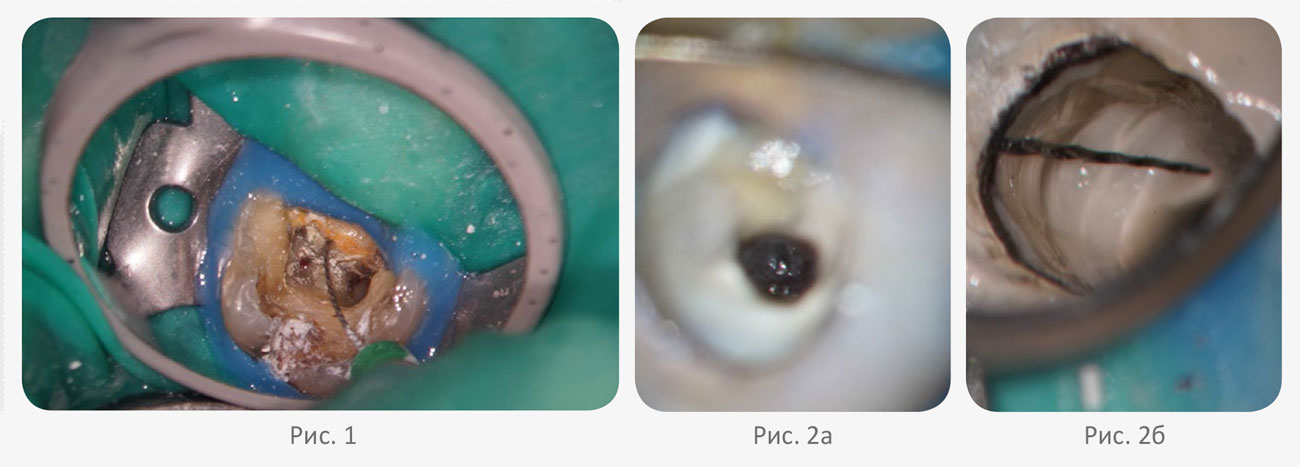

For example, locating the fourth canal in upper molars using a microscope (Fig. 1) clearly yields better results [1]. Certain procedures (Fig. 2) are only possible with a microscope, such as the removal of broken instruments from the canal [2, 3]. A well-recognized advantage (Fig. 3) is the diagnosis of cracks [4]. Retreatment procedures also reach a new level — for extracting fiberglass posts and composite cements from the canal, the microscope is invaluable.

When working with ultrasonic tips inside the canal, the clinician relies not on tactile feedback, but on an objective analysis of the clinical situation (Fig. 4).

Gradually, I realized all the advantages of using an operating microscope in clinical practice.

As a tool that combines optics with coaxial lighting, the microscope undoubtedly improves the quality of endodontic treatment.

For example, locating the fourth canal in upper molars using a microscope (Fig. 1) clearly yields better results [1]. Certain procedures (Fig. 2) are only possible with a microscope, such as the removal of broken instruments from the canal [2, 3]. A well-recognized advantage (Fig. 3) is the diagnosis of cracks [4]. Retreatment procedures also reach a new level — for extracting fiberglass posts and composite cements from the canal, the microscope is invaluable.

When working with ultrasonic tips inside the canal, the clinician relies not on tactile feedback, but on an objective analysis of the clinical situation (Fig. 4).

Orthopedic Aspect

It is widely known that a dentist’s spine is the most vulnerable part of their body during their professional career (Fig. 5).

When used correctly, the microscope allows the clinician to work in the 12 o'clock position. This posture prevents the spine from bending either left or right.

With a properly chosen working distance, the clinician’s back remains straight throughout the procedure, significantly reducing strain and allowing longer, more ergonomic treatments (Fig. 6).

If a doctor tries to avoid proper use of the microscope, the microscope "wins" — it simply ends up unused.

When used correctly, the microscope allows the clinician to work in the 12 o'clock position. This posture prevents the spine from bending either left or right.

With a properly chosen working distance, the clinician’s back remains straight throughout the procedure, significantly reducing strain and allowing longer, more ergonomic treatments (Fig. 6).

If a doctor tries to avoid proper use of the microscope, the microscope "wins" — it simply ends up unused.

Ophthalmologic Aspect

Let’s immediately dismiss the myth that microscopes damage eyesight — in fact, it is the only tool that helps preserve it.

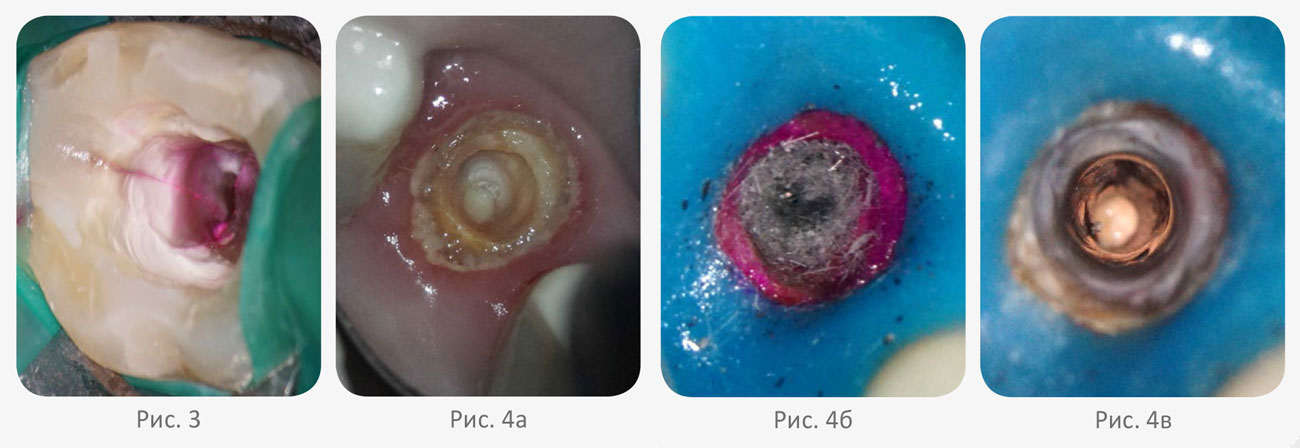

Without a microscope, the eyes must constantly converge on a near object, causing sustained contraction and tension of the medial rectus muscle. Over time, this leads to fatigue and makes it harder for the dentist to concentrate (Fig. 7).

With a microscope, the gaze is directed into infinity, and the microscope’s optics handle convergence (Fig. 8), allowing the dentist to perform more complex procedures with greater precision and for longer periods of time.

Without a microscope, the eyes must constantly converge on a near object, causing sustained contraction and tension of the medial rectus muscle. Over time, this leads to fatigue and makes it harder for the dentist to concentrate (Fig. 7).

With a microscope, the gaze is directed into infinity, and the microscope’s optics handle convergence (Fig. 8), allowing the dentist to perform more complex procedures with greater precision and for longer periods of time.

Psychological Aspect

Over the years, working with patients from different countries and cultures, I have observed various psychological reactions to dental treatment. When the microscope became an integral part of my practice, I noticed patients behaved more calmly during procedures.

At my clinic in Tel Aviv, I often treat patients referred by other doctors, and for most of them, it’s their first time encountering a microscope.

I developed a questionnaire to evaluate the patient's experience during treatment involving a microscope:

Forty people participated in the survey. The results: improvement in subjective sensation and confidence in the doctor (questions 2 and 4) was noted by 36 participants (90%), and 33 of them (82.5%) attributed this to the microscope. Fear levels decreased in 29 patients (72.5%).

Thus, the use of a microscope in endodontic treatment clearly improves the patient’s subjective experience, strengthens their confidence in the dentist, and reduces anxiety.

Let’s try to analyze this series of positive psychological effects. One of the major issues in dentistry is dentophobia. There are many reasons behind it, and one of them is the invasion of personal space.

American researcher Dr. Edward T. Hall explained that every person has their own territorial needs [5]. He defined four personal space zones that most people use:

a) Intimate distance

b) Personal distance

c) Social distance

d) Public distance

These zones represent the spaces we allow others to enter. The intimate zone may be close (touching) or distant (18 to 45 cm), and it is reserved for people we are closest to — parents, children, partners.

During a dental procedure, an uncomfortable invasion of this intimate space occurs, often associated with the risk of pain. On top of that, some patients lose their sense of control.

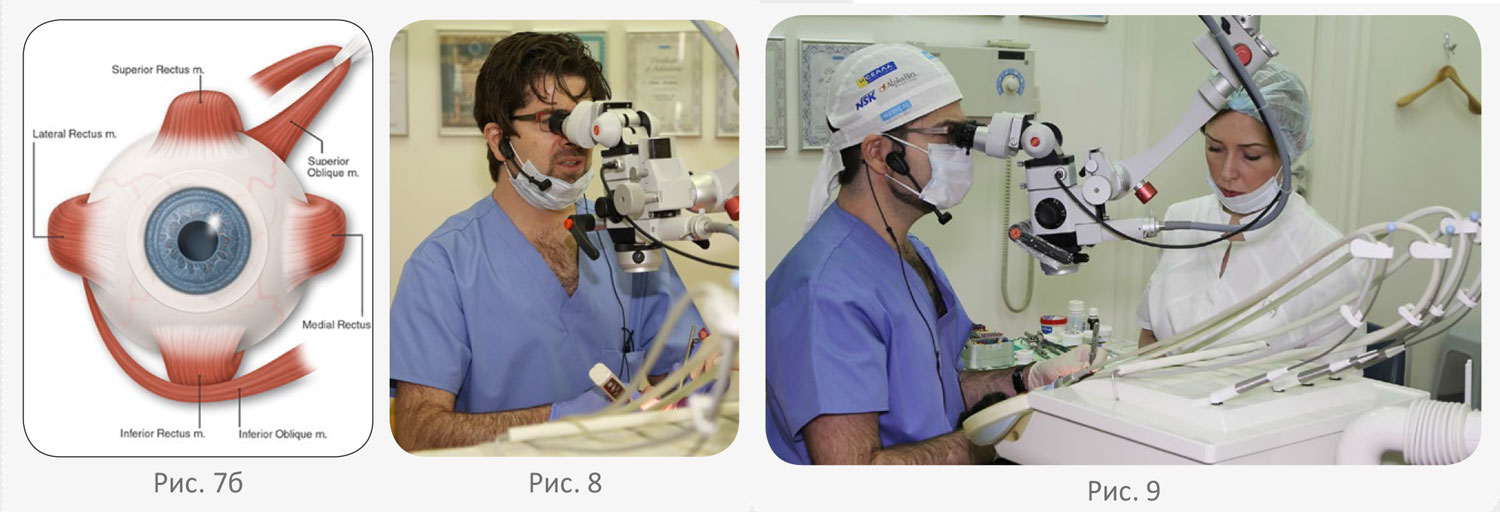

In my opinion, the microscope allows the dentist to avoid entering the patient’s intimate zone — the doctor's face remains more than 50 cm away from the patient's, which significantly changes the psychological dynamics of the treatment (Fig. 9).

In conclusion, after going through the learning curve of using a microscope — which varies for each individual clinician — integrating the microscope into daily practice yields the following benefits:

All these advantages positively affect both treatment outcomes and the overall atmosphere in the dental clinic.

I hope my conclusions will encourage those who are hesitant and help convince those who resist. And of course, those who’ve put their microscopes aside — it’s time to bring them back into battle.

At my clinic in Tel Aviv, I often treat patients referred by other doctors, and for most of them, it’s their first time encountering a microscope.

I developed a questionnaire to evaluate the patient's experience during treatment involving a microscope:

- Fear level during treatment (1 – decreased, 2 – same, 3 – increased).

- Subjective sensation (1 – worsened, 2 – same, 3 – improved).

- If you chose "3" for either question, what do you associate it with?

- Being treated by a specialist

- Use of a rubber dam

- Use of a microscope

- Confidence in the dentist using a microscope (1 – decreased, 2 – same, 3 – increased)

Forty people participated in the survey. The results: improvement in subjective sensation and confidence in the doctor (questions 2 and 4) was noted by 36 participants (90%), and 33 of them (82.5%) attributed this to the microscope. Fear levels decreased in 29 patients (72.5%).

Thus, the use of a microscope in endodontic treatment clearly improves the patient’s subjective experience, strengthens their confidence in the dentist, and reduces anxiety.

Let’s try to analyze this series of positive psychological effects. One of the major issues in dentistry is dentophobia. There are many reasons behind it, and one of them is the invasion of personal space.

American researcher Dr. Edward T. Hall explained that every person has their own territorial needs [5]. He defined four personal space zones that most people use:

a) Intimate distance

b) Personal distance

c) Social distance

d) Public distance

These zones represent the spaces we allow others to enter. The intimate zone may be close (touching) or distant (18 to 45 cm), and it is reserved for people we are closest to — parents, children, partners.

During a dental procedure, an uncomfortable invasion of this intimate space occurs, often associated with the risk of pain. On top of that, some patients lose their sense of control.

In my opinion, the microscope allows the dentist to avoid entering the patient’s intimate zone — the doctor's face remains more than 50 cm away from the patient's, which significantly changes the psychological dynamics of the treatment (Fig. 9).

In conclusion, after going through the learning curve of using a microscope — which varies for each individual clinician — integrating the microscope into daily practice yields the following benefits:

- Higher-quality and more predictable endodontic treatments

- Ability to perform complex endodontic procedures more efficiently

- Improved ergonomics and reduced risk of occupational health issues

- Lower stress levels for patients

All these advantages positively affect both treatment outcomes and the overall atmosphere in the dental clinic.

I hope my conclusions will encourage those who are hesitant and help convince those who resist. And of course, those who’ve put their microscopes aside — it’s time to bring them back into battle.

References

- Baldassari-Cruz L.A., Lilly J.P., Rivera E.M. The influence of dental operating microscopes in locating the mesiolingual canal orifices // Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. — 2002. — Vol. 93. — P. 190–219.

- Ruddle C.J. Nonsurgical retreatmen // S. Cohen, R.C. Burns (eds.). Pathways of the pulp. 8th ed. — St Louis: Mosby, 2002. — P. 875–930.

- Solomonov M. Broken instrument. Clinical decision and techniques of removal // Practical Scientific J. Clinisheskaya Endodotiya (Clinical Endodontics). — 2007. — № 1 [in Russia].

- Clarkc D.J., Sheets Ch.G., Paquette J.M. Definitive Diagnosis of Early Enamel and Dentinal Cracks Based on Microscopic Evaluation // J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. — 2003. — Vol. 15.

- The Hidden Dimension. — Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1966.