Mikhail Solomonov,

director of the Postgraduate Endodontic Program, Department of Endodontics, Sheba Medical Center, Tel HaShomer (Israel);

Lecturer for "Medical Consulting Group" (Moscow)

director of the Postgraduate Endodontic Program, Department of Endodontics, Sheba Medical Center, Tel HaShomer (Israel);

Lecturer for "Medical Consulting Group" (Moscow)

Dens invaginatus ("tooth within a tooth") is a rare anatomical variation, predominantly observed in the maxillary lateral incisors. Due to the complexity of the root canal system structure in dens invaginatus cases, clinicians often face significant challenges in diagnosing and choosing the appropriate treatment approach. The clinical case presented below illustrates the specifics of diagnosing, planning, and treating a Type 3 dens invaginatus using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) analysis.

Introduction

Dens invaginatus is a developmental anomaly described as a "tooth within a tooth" or as a developmental malformation resulting from invagination of the enamel organ prior to calcification. It most frequently affects the maxillary lateral incisors, with a reported prevalence ranging from 0.3% to 10% [1]. The complexity of the root canal system poses a considerable challenge for clinicians. The most commonly used classification was published by Oehlers in 1957 [2]. Various treatment approaches have been described in the literature, including prophylactic sealing, endodontic treatment of the invagination alone, combined treatment of the invagination and the main canal, surgical intervention, or removal of the invaginated structure [3–12].

CBCT is a three-dimensional imaging modality that significantly enhances the diagnostic and treatment planning capabilities for teeth with anatomical variations and complex root canal systems [9,13–14].

This case report demonstrates the role of CBCT in diagnosing, treatment planning, and management of a Type 3 dens invaginatus.

CBCT is a three-dimensional imaging modality that significantly enhances the diagnostic and treatment planning capabilities for teeth with anatomical variations and complex root canal systems [9,13–14].

This case report demonstrates the role of CBCT in diagnosing, treatment planning, and management of a Type 3 dens invaginatus.

Clinical Case

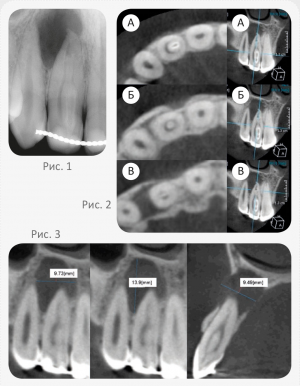

A 22-year-old patient was referred to a private endodontic practice for treatment of tooth 12 with abnormal anatomical structure. The patient reported frequent episodes of pain (at the time of presentation, he was unable to chew or bite food, and percussion of the tooth was sensitive). On examination, a composite restoration and a retention orthodontic splint connecting teeth 13, 12, 11, 21, 22, and 23 were observed on the palatal surface of tooth 12 (Fig. 1). Periodontal probing revealed pocket depths of less than 3 mm, and the tooth’s mobility was within physiological limits. The tooth was sensitive to percussion and palpation and showed no response to cold testing (Endo Ice; ColteneWhaledent Inc, Cuyahoga Falls, OH). Cold testing of adjacent teeth yielded positive results, with no abnormal mobility or percussion sensitivity noted. Radiographic examination revealed that tooth 12 exhibited dens invaginatus morphology, with a radiolucent lesion in the periapical area on the distal side of the root of tooth 12 and the mesial surface of the root of tooth 13. The lesion measured more than 20 mm, and its apical boundary was not visualized (Fig. 1).

The patient was referred for CBCT imaging to determine the precise morphology of the tooth and to assess the size and extent of the lesion. Cross-sectional and longitudinal CBCT scans (Carestream 9300, France) showed that the invagination extended along the entire length of the root. The invagination was embedded in the mesial wall of the root canal, and in the coronal third, the main canal partially surrounded the invagination, creating a C-shaped canal (Fig. 2A). In the middle third, the dens invaginatus was separated from the root dentin, and the main canal completely encircled the invagination (Fig. 2B). In the apical third, two separate canals were observed (Fig. 2C).

According to the CBCT data, the lesion measured 9.73×9.49×13.9 mm (Fig. 3). The lesion had a common boundary with the nasal cavity, the mesial surface of tooth 13, and perforated both the palatal and buccal cortical plates.

Based on clinical and radiographic findings, the diagnosis was: pulp necrosis, symptomatic apical periodontitis, and type 3 dens invaginatus [2].

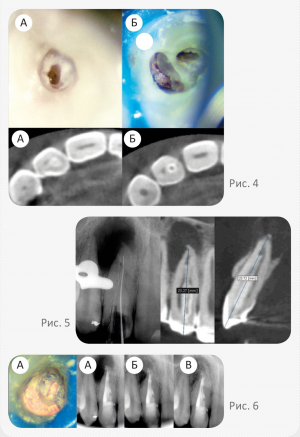

At the first visit, after isolating the tooth with a rubber dam, access to the pulp chamber was created from the palatal surface under an operating microscope, guided by the CBCT data. The first step was creating access by carefully cleaning the palatal groove (Fig. 4A).

The patient was referred for CBCT imaging to determine the precise morphology of the tooth and to assess the size and extent of the lesion. Cross-sectional and longitudinal CBCT scans (Carestream 9300, France) showed that the invagination extended along the entire length of the root. The invagination was embedded in the mesial wall of the root canal, and in the coronal third, the main canal partially surrounded the invagination, creating a C-shaped canal (Fig. 2A). In the middle third, the dens invaginatus was separated from the root dentin, and the main canal completely encircled the invagination (Fig. 2B). In the apical third, two separate canals were observed (Fig. 2C).

According to the CBCT data, the lesion measured 9.73×9.49×13.9 mm (Fig. 3). The lesion had a common boundary with the nasal cavity, the mesial surface of tooth 13, and perforated both the palatal and buccal cortical plates.

Based on clinical and radiographic findings, the diagnosis was: pulp necrosis, symptomatic apical periodontitis, and type 3 dens invaginatus [2].

At the first visit, after isolating the tooth with a rubber dam, access to the pulp chamber was created from the palatal surface under an operating microscope, guided by the CBCT data. The first step was creating access by carefully cleaning the palatal groove (Fig. 4A).

The next step involved entering the main (C-shaped) canal at a bucco-distal angle (Fig. 4B). Necrotic pulp tissue was found in both the invaginated canal and the main canal. The working length was initially determined using CBCT data [15] and later confirmed with an electronic apex locator (Dentaport ZX, Morita, Tokyo, Japan) and a radiographic imaging system (Fig. 5).

Biomechanical preparation of the narrow canal was performed using nickel-titanium (NiTi) rotary instruments G-File (G1, G2, Micro-Mega, Besançon, France) and Revo-S (Micro-Mega, Besançon, France), with irrigation using 3% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution. The main C-shaped canal was treated using the Self-Adjusting File (SAF) 1.5 mm (ReDent-Nova, Ra’anana, Israel) with irrigation using a 3% sodium hypochlorite solution delivered by the VATEA system (ReDent-Nova, Ra’anana, Israel) at 4 ml/min [16].

Final irrigation was performed with 17% EDTA solution, and the root canal was filled with calcium hydroxide paste using a Lentulo spiral filler. The access cavity was temporarily sealed with Cavit (ESPE, Seefeld, Germany) and IRM (Caulk, DeTreyDentsply, Saint-Quentin-Yvelines, France).

At the second visit, two weeks later, the patient was asymptomatic. The calcium hydroxide was removed from the canals by abundant irrigation with sodium hypochlorite solution and the use of SAF [17], followed by final irrigation with EDTA solution.

Both root canals were dried and obturated using a combined technique: the apical third was filled using the lateral compaction technique of gutta-percha with manual NiTi spreaders (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland), and the middle and coronal thirds were filled with the vertical compaction of warm gutta-percha using B&L Alpha (B&L Biotech, Gunpo, Korea) and Machtou pluggers (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). BJM RCS (BJM Laboratory, Or-Yeuda, Israel) was used as the sealer. The access cavity was temporarily sealed with glass ionomer cement Ionomer EQUIA (GC America, Alsip, Ill., USA) (Fig. 6A).

Follow-up examinations at 6 and 18 months showed that the tooth remained asymptomatic, with no sensitivity to percussion or palpation, normal tooth mobility, and periodontal pocket depths within physiological limits. Radiographic examination demonstrated continued healing of the lesion (Fig. 6B, C).

Biomechanical preparation of the narrow canal was performed using nickel-titanium (NiTi) rotary instruments G-File (G1, G2, Micro-Mega, Besançon, France) and Revo-S (Micro-Mega, Besançon, France), with irrigation using 3% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution. The main C-shaped canal was treated using the Self-Adjusting File (SAF) 1.5 mm (ReDent-Nova, Ra’anana, Israel) with irrigation using a 3% sodium hypochlorite solution delivered by the VATEA system (ReDent-Nova, Ra’anana, Israel) at 4 ml/min [16].

Final irrigation was performed with 17% EDTA solution, and the root canal was filled with calcium hydroxide paste using a Lentulo spiral filler. The access cavity was temporarily sealed with Cavit (ESPE, Seefeld, Germany) and IRM (Caulk, DeTreyDentsply, Saint-Quentin-Yvelines, France).

At the second visit, two weeks later, the patient was asymptomatic. The calcium hydroxide was removed from the canals by abundant irrigation with sodium hypochlorite solution and the use of SAF [17], followed by final irrigation with EDTA solution.

Both root canals were dried and obturated using a combined technique: the apical third was filled using the lateral compaction technique of gutta-percha with manual NiTi spreaders (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland), and the middle and coronal thirds were filled with the vertical compaction of warm gutta-percha using B&L Alpha (B&L Biotech, Gunpo, Korea) and Machtou pluggers (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). BJM RCS (BJM Laboratory, Or-Yeuda, Israel) was used as the sealer. The access cavity was temporarily sealed with glass ionomer cement Ionomer EQUIA (GC America, Alsip, Ill., USA) (Fig. 6A).

Follow-up examinations at 6 and 18 months showed that the tooth remained asymptomatic, with no sensitivity to percussion or palpation, normal tooth mobility, and periodontal pocket depths within physiological limits. Radiographic examination demonstrated continued healing of the lesion (Fig. 6B, C).

Discussion

Dens invaginatus presents a significant challenge for clinicians due to the complex root canal anatomy. It is a developmental anomaly most often affecting maxillary lateral incisors and less commonly premolars [18–19]. Treatment approaches include prophylactic, endodontic, or surgical options, depending on the complexity [3–12].

Today, CBCT enables three-dimensional imaging of teeth with complex canal anatomies [9,13–14], influencing treatment planning decisions. ALARA principles suggest minimizing radiation exposure, thus CBCT scans for follow-up are not routinely required.

In this case, CBCT showed that the invagination occupied most of the canal, fused with the medial wall coronally, and separated in the middle third. Complete removal of the invagination was not feasible and would risk significant dentin loss, compromising tooth structure [20–21].

The C-shaped configuration of the main canal and the narrow round shape of the invagination canal were confirmed across multiple planes. Thus, a conservative approach was selected: treating both canals with appropriate instruments — SAF for the C-shaped canal [16] and NiTi rotary files for the invaginated canal.

Warm vertical compaction of gutta-percha was used to fill spaces adjacent to the invagination, as seen in postoperative radiographs. We assume that the combination of NaOCl and calcium hydroxide successfully dissolved the necrotic pulp tissue [22–29].

Today, CBCT enables three-dimensional imaging of teeth with complex canal anatomies [9,13–14], influencing treatment planning decisions. ALARA principles suggest minimizing radiation exposure, thus CBCT scans for follow-up are not routinely required.

In this case, CBCT showed that the invagination occupied most of the canal, fused with the medial wall coronally, and separated in the middle third. Complete removal of the invagination was not feasible and would risk significant dentin loss, compromising tooth structure [20–21].

The C-shaped configuration of the main canal and the narrow round shape of the invagination canal were confirmed across multiple planes. Thus, a conservative approach was selected: treating both canals with appropriate instruments — SAF for the C-shaped canal [16] and NiTi rotary files for the invaginated canal.

Warm vertical compaction of gutta-percha was used to fill spaces adjacent to the invagination, as seen in postoperative radiographs. We assume that the combination of NaOCl and calcium hydroxide successfully dissolved the necrotic pulp tissue [22–29].

Conclusion

This clinical case highlights the importance of CBCT in the planning and management of endodontic treatment in cases of complex root canal anatomy.

Originally published in the journal Endodontia, No. 1–2/2015. Special thanks to Editor-in-Chief Alexey Bolyachin for providing the material.

Originally published in the journal Endodontia, No. 1–2/2015. Special thanks to Editor-in-Chief Alexey Bolyachin for providing the material.

References

1. Alani A., Bishop K. Dens invaginatus. Part 1: classification, prevalence and aetiology // Int. Endod. J. — 2008. — Vol. 41. — P. 1123–1136.

2. Oehlers F.A. Dens invaginatus. I. Variations of the invagination process and associated anterior crown forms // Oral. Surg. Ora.l Med. Oral. Pathol. — 1957. — Vol. 10. — 1204–1218.

3. Holtzman L. Conservative treatment of supernumerary maxillary incisor with dens invaginatus // J. Endod. — 1998. — Vol. 24. — Р. 378–380.

4. de Sousa S.M., Bramante C.M. Dens invaginatus: treatment choices // Endod Dent Traumatol. — 1998. — Vol. 14. — Р. 152–158.

5. Tsurumachi T., Hayashi M., Takeichi O. Non-surgical root canal treatment of dens invaginatus type 2 in a maxillary lateral incisor // Int. Endod. J. — 2002. — Vol. 35. — Р. 310–314.

6. Creaven J. Dens invaginatus-type malformation without pulpal involvement // J. Endod. — 1975. — Vol. 1. — Р. 79–80.

7. Kulild J.C., Weller R.N. Treatment considerations in dens invaginatus // J. Endod. — 1989. — Vol. 15. — Р. 381–384.

8. Skoner J.R., Wallace J.A. Dens invaginatus: another use for the ultrasonic // J. Endod. — 1994. — Vol. 20. — Р. 138–140.

9. Kfir A., Telishevsky-Strauss Y., Leitner A., Metzger Z. The diagnosis and conservative treatment of a complex type 3 dens invaginatus using cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and 3D plastic models // Int. Endod. J. 2013. — Vol. 46. — Р. 275–288.

10. Vier-Pelisser F.V., Pelisser A., Recuero L.C., Só M.V., Borba M.G., Figueiredo J.A. Use of cone beam computed tomography in the diagnosis, planning and follow up of a type III dens invaginatus case // Int. Endod. J. — 2012. — Vol. 45. — Р. 198–208.

11. Narayana P., Hartwell G.R., Wallace R., Nair U.P. Endodontic clinical management of a dens invaginatus case by using a unique treatment approach: a case report // J. Endod. — 2012. — Vol. 38. — Р. 1145–1148.

12. da Silva Neto U.X., Hirai V.H., Papalexiou V., Gonçalves S.B., Westphalen V.P., Bramante C.M., Martins W.D. Combined endodontic therapy and surgery in the treatment of dens invaginatus Type 3: case report // J. Can. Dent. Assoc. — 2005. — Vol. 71. — Р. 855–858.

13. Durack C., Patel S. The use of cone beam computed tomography in the management of dens invaginatus affecting a strategic tooth in a patient affected by hypodontia: a case report // Int. Endod. J. — 2011. — Vol. 44. — Р. 474–483.

14. Patel S. The use of cone beam computed tomography in the conservative management of dens invaginatus: a case report // Int. Endod. J. — 2010. — Vol. 43. — Р. 707–713.

15. Jeger F.B., Janner S.F., Bornstein M.M., Lussi A. Endodontic working length measurement with preexisting cone-beam computed tomography scanning: a prospective, controlled clinical study // J. Endod. — 2012. — Vol. 38. — Р. 884–888.

16. Solomonov M., Paqué F., Fan B., Eilat Y., Berman L.H. The challenge of C-shaped canal systems: a comparative study of the self- adjusting file and ProTaper // J. Endod. — 2012. — Vol. 38. — Р. 209–214.

17. Topçuoğlu H.S., Düzgün S., Ceyhanlı K.T., Aktı A., Pala K., Kesim B. Efficacy of different irrigation techniques in the removal of calcium hydroxide from a simulated internal root resorption cavity // Int. Endod. J. — 2014, May 25 [Epub. ahead of print].

18. Al Omari F., Al-Omari I.K. Cleft lip and palate in Jordan: birth prevalence rate // Cleft Palate Craniofac J. — 2004. — Vol. 41. — Р. 609–612.

19. Tagger M. Nonsurgical endodontic therapy of tooth invagination. Report of a case // Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. — 1977. — Vol. 43. — Р. 124–129.

20. Sornkul E., Stannard J.G. Strength of roots before and after endodontic treatment and restoration // J. Endod. — 1992. — Vol. 18. — Р. 440–443.

21. Krishan R., Paqué F., Ossareh A., Kishen A., Dao T., Friedman S. Impacts of conservative endodontic cavity on root canal instrumentation efficacy and resistance to fracture assessed in incisors, premolars, and molars // J. Endod. 2014. — Vol. 40, N 8. — Р. 1160–1166.

22. Hasselgren G., Olsson B., Cvek M. Effects of calcium hydroxide and sodium hypochlorite on the dissolution of necrotic porcine muscle tissue // J. Endod. — 1988. — Vol. 14. — Р. 125–127.

23. Türkün M., Cengiz T. The effects of sodium hypochlorite and calcium hydroxide on tissue dissolution and root canal cleanliness // Int. Endod. J. 1997. — Vol. 30. — Р. 335–342.

24. Wadachi R., Araki K., Suda H. Effect of calcium hydroxide on the dissolution of soft tissue on the root canal wall // J. Endod. — 1998. — Vol. 24. — Р. 326–330.

25. Andersen M., Lund A., Andreasen J.O., Andreasen F.M. In vitro solubility of human pulp tissue in calcium hydroxide and sodium hypochlorite // Endod. Dent. Traumatol. — 1992. — Vol. 8. — Р. 104–108.

26. De-Deus G., Barino B., Marins J., Magalhães K., Thuanne E., Kfir A. Self-adjusting file cleaning-shaping-irrigation system optimizes the filling of oval-shaped canals with thermoplasticized gutta-percha // J. Endod. — 2012. — Vol. 38. — Р. 846–849.

27. Siqueira J.F. Jr, Alves F.R., Almeida B.M., de Oliveira J.C., Rôças I.N. Ability of chemomechanical preparation with either rotary instruments or self-adjusting file to disinfect oval-shaped root canals // J. Endod. — 2010. — Vol. 36. — Р. 1860–1865.

28. Wu M.K., Kast’áková A., Wesselink P.R. Quality of cold and warm gutta-percha fillings in oval canals in mandibular premolars // Int. Endod. J. — 2001. — Vol. 34. — Р. 485–491.

29. Metzger Z., Zary R., Cohen R., Teperovich E., Paque F. The quality of root canal preparation and root canal obturation in canals treated with rotary versus self-adjusting files: a three-dimensional micro-computed tomographic study // J. Endod. — 2010. — Vol. 36. — Р. 1569–1573.

2. Oehlers F.A. Dens invaginatus. I. Variations of the invagination process and associated anterior crown forms // Oral. Surg. Ora.l Med. Oral. Pathol. — 1957. — Vol. 10. — 1204–1218.

3. Holtzman L. Conservative treatment of supernumerary maxillary incisor with dens invaginatus // J. Endod. — 1998. — Vol. 24. — Р. 378–380.

4. de Sousa S.M., Bramante C.M. Dens invaginatus: treatment choices // Endod Dent Traumatol. — 1998. — Vol. 14. — Р. 152–158.

5. Tsurumachi T., Hayashi M., Takeichi O. Non-surgical root canal treatment of dens invaginatus type 2 in a maxillary lateral incisor // Int. Endod. J. — 2002. — Vol. 35. — Р. 310–314.

6. Creaven J. Dens invaginatus-type malformation without pulpal involvement // J. Endod. — 1975. — Vol. 1. — Р. 79–80.

7. Kulild J.C., Weller R.N. Treatment considerations in dens invaginatus // J. Endod. — 1989. — Vol. 15. — Р. 381–384.

8. Skoner J.R., Wallace J.A. Dens invaginatus: another use for the ultrasonic // J. Endod. — 1994. — Vol. 20. — Р. 138–140.

9. Kfir A., Telishevsky-Strauss Y., Leitner A., Metzger Z. The diagnosis and conservative treatment of a complex type 3 dens invaginatus using cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and 3D plastic models // Int. Endod. J. 2013. — Vol. 46. — Р. 275–288.

10. Vier-Pelisser F.V., Pelisser A., Recuero L.C., Só M.V., Borba M.G., Figueiredo J.A. Use of cone beam computed tomography in the diagnosis, planning and follow up of a type III dens invaginatus case // Int. Endod. J. — 2012. — Vol. 45. — Р. 198–208.

11. Narayana P., Hartwell G.R., Wallace R., Nair U.P. Endodontic clinical management of a dens invaginatus case by using a unique treatment approach: a case report // J. Endod. — 2012. — Vol. 38. — Р. 1145–1148.

12. da Silva Neto U.X., Hirai V.H., Papalexiou V., Gonçalves S.B., Westphalen V.P., Bramante C.M., Martins W.D. Combined endodontic therapy and surgery in the treatment of dens invaginatus Type 3: case report // J. Can. Dent. Assoc. — 2005. — Vol. 71. — Р. 855–858.

13. Durack C., Patel S. The use of cone beam computed tomography in the management of dens invaginatus affecting a strategic tooth in a patient affected by hypodontia: a case report // Int. Endod. J. — 2011. — Vol. 44. — Р. 474–483.

14. Patel S. The use of cone beam computed tomography in the conservative management of dens invaginatus: a case report // Int. Endod. J. — 2010. — Vol. 43. — Р. 707–713.

15. Jeger F.B., Janner S.F., Bornstein M.M., Lussi A. Endodontic working length measurement with preexisting cone-beam computed tomography scanning: a prospective, controlled clinical study // J. Endod. — 2012. — Vol. 38. — Р. 884–888.

16. Solomonov M., Paqué F., Fan B., Eilat Y., Berman L.H. The challenge of C-shaped canal systems: a comparative study of the self- adjusting file and ProTaper // J. Endod. — 2012. — Vol. 38. — Р. 209–214.

17. Topçuoğlu H.S., Düzgün S., Ceyhanlı K.T., Aktı A., Pala K., Kesim B. Efficacy of different irrigation techniques in the removal of calcium hydroxide from a simulated internal root resorption cavity // Int. Endod. J. — 2014, May 25 [Epub. ahead of print].

18. Al Omari F., Al-Omari I.K. Cleft lip and palate in Jordan: birth prevalence rate // Cleft Palate Craniofac J. — 2004. — Vol. 41. — Р. 609–612.

19. Tagger M. Nonsurgical endodontic therapy of tooth invagination. Report of a case // Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. — 1977. — Vol. 43. — Р. 124–129.

20. Sornkul E., Stannard J.G. Strength of roots before and after endodontic treatment and restoration // J. Endod. — 1992. — Vol. 18. — Р. 440–443.

21. Krishan R., Paqué F., Ossareh A., Kishen A., Dao T., Friedman S. Impacts of conservative endodontic cavity on root canal instrumentation efficacy and resistance to fracture assessed in incisors, premolars, and molars // J. Endod. 2014. — Vol. 40, N 8. — Р. 1160–1166.

22. Hasselgren G., Olsson B., Cvek M. Effects of calcium hydroxide and sodium hypochlorite on the dissolution of necrotic porcine muscle tissue // J. Endod. — 1988. — Vol. 14. — Р. 125–127.

23. Türkün M., Cengiz T. The effects of sodium hypochlorite and calcium hydroxide on tissue dissolution and root canal cleanliness // Int. Endod. J. 1997. — Vol. 30. — Р. 335–342.

24. Wadachi R., Araki K., Suda H. Effect of calcium hydroxide on the dissolution of soft tissue on the root canal wall // J. Endod. — 1998. — Vol. 24. — Р. 326–330.

25. Andersen M., Lund A., Andreasen J.O., Andreasen F.M. In vitro solubility of human pulp tissue in calcium hydroxide and sodium hypochlorite // Endod. Dent. Traumatol. — 1992. — Vol. 8. — Р. 104–108.

26. De-Deus G., Barino B., Marins J., Magalhães K., Thuanne E., Kfir A. Self-adjusting file cleaning-shaping-irrigation system optimizes the filling of oval-shaped canals with thermoplasticized gutta-percha // J. Endod. — 2012. — Vol. 38. — Р. 846–849.

27. Siqueira J.F. Jr, Alves F.R., Almeida B.M., de Oliveira J.C., Rôças I.N. Ability of chemomechanical preparation with either rotary instruments or self-adjusting file to disinfect oval-shaped root canals // J. Endod. — 2010. — Vol. 36. — Р. 1860–1865.

28. Wu M.K., Kast’áková A., Wesselink P.R. Quality of cold and warm gutta-percha fillings in oval canals in mandibular premolars // Int. Endod. J. — 2001. — Vol. 34. — Р. 485–491.

29. Metzger Z., Zary R., Cohen R., Teperovich E., Paque F. The quality of root canal preparation and root canal obturation in canals treated with rotary versus self-adjusting files: a three-dimensional micro-computed tomographic study // J. Endod. — 2010. — Vol. 36. — Р. 1569–1573.